BY RUCHIRA GHOSH

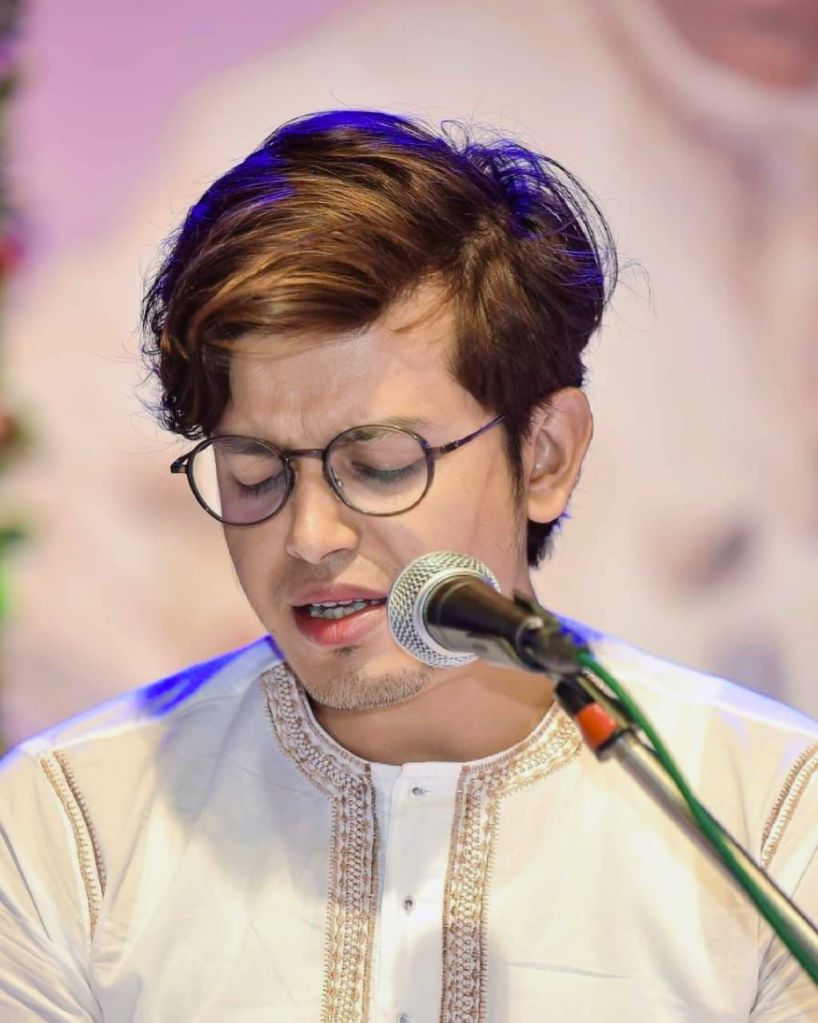

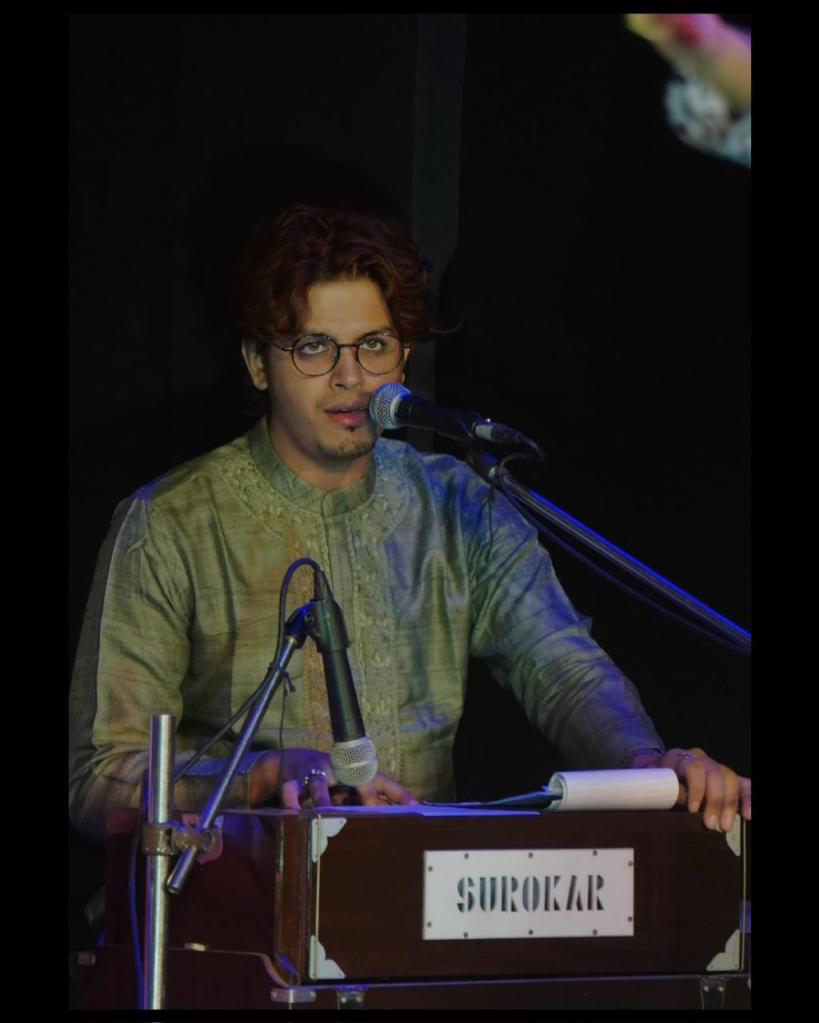

Nearly three years ago, at a grand musical event organized by a prominent local choir, Swarchhanda (lit. symphony & rhythm), I had the opportunity to hear the young Kolkata-based vocalist Jaydeep Sinha. And trust me, I was enthralled. His flawless, mellifluous rendition of “Mere Dhoond Dal Saaje” in pure Hindustani classical mode—on which Tagore based his creation “Maharaj Eki Saaje” (which he sang next)—charmed the audience no end. Recently, Jaydeep was in town to participate in a string of cultural events, notably the gala Theatre Festival organized by the National School of Drama. We met on the sidelines of the fest, and an interesting conversation ensued. Read on…

How was your childhood? Was there music in the family? Who or what inspired you?

I was born in the late 1980s in a suburb of Calcutta, shortly before India’s economic liberalization and globalization. There were no cell phones or the internet, and life was much simpler and more joyful. Middle-class morality played a significant role in shaping our upbringing. My mother learned music before her marriage, but she couldn’t continue due to unfavorable circumstances. Her father played the esraj, but he had to leave it behind in Dhaka because of a stormy exodus post-partition of 1947. My elder sibling learned vocal music. I was barely three years old, so I wasn’t very interested. Nevertheless, one day I flawlessly sang a bandish that my sister was trying but couldn’t manage. This made my mother realize that I had talent, and she initially taught me the very basics.

A sketch of your academics and how you juggled them with music?

I always kept music as a subject until my undergraduate studies, to avoid the flimsy excuse of studies getting hampered once I reached the secondary level. I consistently received good marks in music, even achieving the highest scores in the board exams. I even changed my old school and friends just to take music as a subject because it was neither offered nor had a teacher. This, coupled with some family issues, affected my mental health. With a dash of regular taalim (music lessons) just before the exams began, I performed well. I loved Geography and performed well in it, which inspired me to pursue an honours degree in Geography. Once again, I chose a college that would allow me to take music as a pass subject, and we had to go to the Bengal Music College (under the University of Calcutta), which was quite far from my undergraduate college. Music has always helped me in my studies.

Trace your musical journey: guru shishya parampara, Western music, Hindustani classical, and their influence on you. How was your first public performance/debut, and what was the response/feedback?

Like I mentioned earlier, my older sister was studying under a music teacher; I would listen to her taalim during practice sessions at home. One day, the teacher asked her to sing a bandish, and I sang it before her, which led to my talent being recognized. My learning began with Hindustani Classical Music (mainly from Maa), and during high school, I began learning Rabindrasangeet from Professor Anil Ranjan Guha. After his sudden demise, Mom insisted that we zero in on the legendary Rabindrasangeet singer and mentor Maya Sen, who was a reputed teacher. Eventually, having traced Maya Di’s whereabouts, we managed to meet her. In her presence, I sang “Ami Ki Naam Gaabo Je Bebe Na Paai” (sort of a test it was). Maya Di was impressed and took me on. She was an incredible teacher. Her style, attention to detail, and personal attention to each pupil were indeed amazing. Alongside, I studied Hindustani music under the Kotali Gharana. I attended live concerts in Calcutta every winter. Eventually, my mother felt I needed a more proficient guru and asked Maya Di for a recommendation. She directed me to learn from Dr. Samiran Chatterjee, of the Indore gharana and a disciple of Pt. Srikant Bakre. Coincidentally, both of my gurus were disciples of the Dhrupad maestro, Ustad Fahimuddin Dagar Sahib. I never had the typical Ganda Bandhana ceremony since Maya Di believed that external displays of devotion toward gurus were unnecessary.

Your public performances?

My first public performance was during a competition in my hometown. I remember confidently singing a Nazrul Geeti titled “Palash Phuler Mou.” I began performing professionally on stage much later, in 2014, starting with theatre in Kolkata. The first play in which I sang was “Raktabhumi Premparab Katha,” directed by Manish Mitra, which premiered at Madhusudan Mancha, Kolkata. I gained widespread recognition in the city and beyond by singing in his celebrated play “Urubhangam.” Earlier, I participated in the All India Radio Music Competition for Ghazals in 2009, earning a B General grade from Prasar Bharati, and performed on the radio many times.

Your status quo at this point in time: teaching, performing, practising, logistics, livelihood, grants, funds, sponsorship, fellowship—anything else that is relevant to the issue?

Yes, I have been teaching over the past few years. Most of my students are kids who turn out to be delightful companions. However, as I need time for stage performances and recordings, my teaching is limited. Following Maya Di’s teaching method, I try to give individual attention to all my students. I equally perform classical dance and theatre. The typical world of vocal music rarely calls me, so I am not too visible there, and I do not approach anybody for a piggyback ride. Whenever I get time, I practice. I never miss out on the basic riyaz before recordings and performances.

I had a stint as a part-time regional manager of a music label for a few years. Now I can manage well with performances and teaching.

I have not applied for any grants, funds, sponsorship, or fellowship yet, but I have silently witnessed mismanagement and corruption regarding salary and grants while being part of a theatre group.

Your views on the current vocal music scenario in India… how do you visualize the future?

When it comes to playback singing in the Hindi film industry, I find myself less attracted to it now than I was in the 90s or earlier. Many singers tend to mimic the tone and style of celebrity singers, and as a result, genuine melody seems to be fading. Tuneful diversity is diminishing, and essential aspects like “khada sa lagana,” clear pronunciation, “shuddh aakaar,” and breath control while singing appear to be neglected.

Regarding Hindustani classical vocal, I find Maharashtra-based artists are doing pretty well, though mostly copying their gurus’ gayaki. One’s own style is not developing widely. There’s no dearth of talent, but after a point, it’s monotonous.

I am not pessimistic about the future. Maybe this is just a passing phase. Socio-economic changes do affect our music. Change is obvious, and we must accept it.

What is music to you?

I don’t perform rituals, but I feel music is the easiest way to reach the Almighty. It is also a therapy that works as medicine when I am in the throes of depression. I have gone through depression at one stage of my life when I could not sing for many days. Whenever I feel low, a bit of riyaz heals me. Music is also a medium of communication for introverts like me.

Which vocalists do you idolize, appreciate, or admire?

My list is pretty long (laughs). I enjoy songs of Whitney Houston, Josh Groban, Andrea Bocelli, Elvis, Nat King Cole, Celine Dion, Pavarotti, Celia Cruz, Mariah Carey, and many more (pauses). I listen to diverse genres—playback, world music, blues, jazz, rap, hip-hop, rock, folk, and country—to appreciate the nuances of expression and technique.

I idolize Ustad Amir Khan, not only because he is my guru’s ancestral teacher, but also due to his pioneering experiments and heavenly renditions that are available to us.

In the realm of ghazal, one cannot overlook Ustad Mehdi Hassan Sahib’s gayaki; he is truly an institution in this genre. For thumri gayaki, Akhtar Bai, Farida Khanum Sahiba, and Madhurani Ji have always inspired me.

As for thumri, dadra, kaajri, chaiti, holi, barahmasa, my favourites include Shobha Gurtu, Nirmala Devi, Lakshmi Shankar, Sipra Bose, Pt. Chhannulal Mishra, among many.

For Rabindrasangeet, I draw inspiration from Debabrata Biswas and Geeta Ghatak’s renditions. Suchitra Mitra was Maya Di’s idol and senior colleague, and so was Mohor Di (Kanika Banerjee). Swagatalakshmi Dasgupta, who is my guru bon (senior disciple of my guru), and Jayati Chakraborty also figure on my list of favourites.

When not singing, what are you busy with?

Reading, watching series/movies/documentaries, listening to music, watching cookery shows, photography, singing parodies, gossiping with close friends, working out at times, brainstorming on new original compositions, and so on (laughs).

Awards, accolades, citations to date?

- Tagore Foundation Jugal Srimal Scholarship (Rabindrasangeet and Nazrulgeeti) twice

- Music 2000 competition winner in Nazrulgeeti

- Tapan Gupta Smriti Puraskar twice, awarded by Guru Maya Sen

- All India Radio Music Competition winner in Ghazal (2009)

You appear to harbor a passion for the sea, ocean… do you find a link between roaring ocean waters and music?

A seaside sojourn is good only for two or three days; then it gets boring. But yes, I find a healing property in the sound of sea waves. I am more of a mountain person. The Himalayas attract me more than the Bay of Bengal.

As a Bengali, what is the role of food in your life… “If music be the food of love…”?

I eat everything, without any bias regarding edibles or food habits. Though not a foodie per se, I love to taste different types of dishes, besides exploring local, regional, as well as global cuisines. I have a hiatus hernia, so I only avoid a limited number of items to control my acidity. Acidity is poison for a vocalist, as you might know.

Any message to Gen Z, Gen Alpha, etc.?

Today’s kids have a low attention span. They are victims of present situations; however, their guardians need to work on this. Kids need proper quality time to spend with their friends while playing, as we did in our childhood. They should learn to be patient and to be good listeners.

The new generation has the advantage of the internet. A huge repertoire is just a click away; that’s why most of them do not value the easily available resource. We had limited resources, which we used to gather after a lot of hardships, so we valued them. This value system needs to be incorporated in today’s youngsters. Kids are like vessels, innocent as flowers. It’s the responsibility of guardians to mould and shape them and steer them towards good quality music. Also, the future must learn and respect their mother tongues. Here, the guardians need to play a pivotal role.