BY DR KAUSTAV BHATTACHARYYA

AT THE COURT OF KOREA – NOT SO UNDIPLOMATIC MEMORIES

William Sands was assigned to an advisory role at the tender age of 25 to the Emperor of Korea after spending a few years on a US diplomatic mission to the Far-East region, which was the turning point or milestone in his diplomatic career. As John Hay his Secretary of State beautifully summarized in a note sent on the confirmation of the position, “You are an adventurer as far as we are concerned’’ which is the spirit precisely reflected in his memoirs “At the Court of Korea”.

William Sands emerges as the adventurer-explorer diplomat in the long tradition of Lawrence of Arabia and a few others of the late 19th century and early 20th century’s world of diplomacy; of the intrigue and rivalry of the Imperial powers of the likes of Britain, US, Russia and Japan.

William Sands

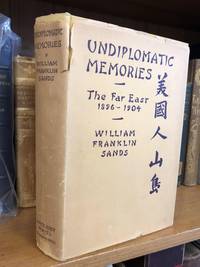

These chronicles of a US Diplomat posted in the Far East titled “Undiplomatic Memories” are during those “innocent years” or “glorious period” of stable Empires when the Great Power rivalry hadn’t yet broken out into a full-blown catastrophic conflict as was the Great War of 1914. Sands’ personalized account provides us an insight into the milieu where Japan as the rising power of Asia with imperial ambitions had just started meddling in the internal affairs of its neighbours.

As a matter of fact, in one of the chapters on the Diplomatic Corps in Seoul, Sands claims to have had a first-hand experience of the ‘machinery of imperialism’ which provided the framework for conducting diplomatic affairs; for instance, most of the foreign legations and their colonies were located strategically in sites which provided the possibility of an easy retreat in the case of an outbreak of hostility.

The desire to witness or rather participate in the emergence of a modern, progressive Korea remains evident in his chronicles.

The emoluments offered by the Emperor for his advisory role were meagre in tune with the diktat on salaries of Imperial advisors imposed by the Japanese regime to restrict the American influence in Korea which was a stumbling block to their complete annexation of the Hermit Kingdom.

In his concluding chapter, which is the most interesting one since he describes the tremors felt about the most calamitous and momentous event of that period, the Russian-Japanese War of 1905, Sands expresses lament in a self-reflective mood about his inability to implement successful administrative reforms and eliminate official bribery. Sands elaborates further on his desire to create a trained cadre of Korean officials for effective, fair and just rural administration along the lines of the British Indian Civil Services, in which he failed. Korea was the site of what we would call in contemporary geopolitical parlance great Power Rivalry between two great Empires of the past, China and Japan and one relatively new entrant in Asia, the Russian Empire.

Particularly the Japanese “meddling” and notoriety in conducting its affairs of foreign policy with the Koreans was glaringly evident to Sands. The insidious game plan of “annexation of Korea” was very much on the cards and consistent efforts were being made in that direction with the Japanese “hand” being very much visible even in the affairs of the provinces, which Sands ascribes one of the reasons for scuttling of his plan for creation of a trained cadre of Administration officials.

While reading through the pages of the book, there emerges a single-minded, dogged focus of Sands on the neutralization of Korea in case of a conflict and the signing of multilateral peace treaties. There was a genuine risk of a war between Russia and Japan and this is a leitmotif through the entire book and Sands attempts to prevent it single-handedly and expresses in his own words: “Looking back at it now, I rather like the gesture. I went into it with my eyes wide open as they could be at the time, though certainly I could not see where it was all leading and I doubt that anyone else could.”

Here the US had a warm, beneficial and benevolent influence on Korea and had envisioned the role of a mediator between the Koreans and Japan and Europe. In order to achieve this broader goal, the twin priorities were better Administration and General Education which were not really existent in Korea. Education played a role in the selection of Bureaucracy which was done through conducting of annual competitive examinations which focused on literature and Classics, completely ignoring modern knowledge. In order to rectify this lacunae, Sands tried to connect all the educational institutions run by the European missionaries in order to create a new curriculum for the administrators. One area of training and education where this model was successful was in the sphere of military men who were being churned from the Military Academy, the first of its kind of professionally trained military men; the Academy was inspired by the ideas from General Dye who provided them with a template about organizing a Cadet school. Sands in his role as the advisor to the Emperor in Korea was close to these military men; riding with them, shooting with them, which incidentally was only allowed for the military officers and going hunting. He even created a small club for them in his garden where there is a funny anecdote of finding some of these sturdy lieutenants and cadet graduates being knocked out after a nocturnal bash. Sands curiously investigated the source of that ‘fatigue effect’ and it was found that they drank the absinthe raw and undiluted.

Here again Sands furnishes us with fantastic unusual insight about how the American missionaries were perceived to be ‘messengers of knowledge’ or ‘carriers of science’ and were engaged in the promotion of Westernization of the native through Reform and Rebellion unlike the French missions which were obscurantists. The asceticism, contemplation and ritual of the monastic life held a broader appeal to the Eastern mind according to Sands. The American missions with their ideal of a simple, humanitarian, ethical life appealed to many of the Easterners including the Koreans. They provided an easy access to Western knowledge, a kind of ‘ride to Western knowledge’ as described in the book.

Sands displays great respect and regard for the average Korean person and he appreciates the courage of the Korean soldiers and saw the ‘making of the good man’ or a rather, sturdy honourable in the Korean peasant even though as fighters they were tardy and weapons were archaic. In the book he reposes his faith which turned prophetic looking back in hindsight since the meteoric rise of Korea as a nation with the statement that “The simple Korean countryman was capable of great development”. In his role as a Court Advisor Sands took great pains to learn about the life of the average Korean or the masses by travelling widely and living amongst them sans any diplomatic trappings of privilege.

The book brings out the elements of Korean feudalism of the early 20th century; while visiting the Southernmost Korean port of Quelpaert Sands brought along a descendant of the Ko family who were the ancient Kings of Quelpaert, Ko Hei Kung. Apparently, his Ko family name carried more weight and ensured security and safety than in the words of Sands “a hundred ragamuffin soldiers with single-shot rifles salvaged from the Franco-Prussian War” since his family was until then worshipped at a temple built in the port city. He mentions about one of his translators hailing from a minor noble family, Ko Hei Kung who was smart and articulate in English but not widely travelled and during his visit to England he impressed the mandarins of the English Court especially the Conservative ones and they invited him over to stay at their homes. Sands shares a Korea proverb in the context of Ko that “a gentleman is known though he be naked in the desert”.

Most interestingly there is a leitmotif of the Japanese chivalry, valour in their military spirit evident through the textual narrative of the book. Clearly Sands had fallen in love and admiration for the proverbial “Samurai” spirit of the Japanese upon which the foundation of their military is built. This was a period when Japanese military ambitions were on the ascendancy and their model was that of the ‘Renin’, that proverbial fiercely independent spirit and masterless man of the old days of the clan rivalry. The Japanese Royal Court was known for its rigidity and the people came across as courteous, orderly and friendly to a foreign observer. Most interesting or rather the fascinating part for me as a reader was the captivating account of the landing of the Japanese troops and their marching onto Korean soil which according to Sands ‘landed like clockwork’.

The same Japanese fighting machine which wreaks unprecedented havoc in the Pacific theatre of conflict and Asia a decade later. In the eyes of the author the spectacle of the Japanese army marching in 1904 was far finer and magnificent spectacle as compared to the jackboots of the Kaiser’s Army marching into Belgium in the Great War. He praises the “self-discipline” of the Japanese which is inherently organic and natural and sees that the Japanese are courteous and considerate when dealing with the natives of the land or the ‘occupied’. This courtly martial dignified image of the Japanese army undergoes a drastic change during the next 4 decades and is completely sullied by records of atrocities and dishonour. Importantly the Asian powers like China were impressed by the Japanese’ successful and seamless absorption of Western Science and Knowledge system.

This is being in complete contrast to what Sands had to say about the Russian warrior ethos, debunking it as the ‘unprincipled strength of the whole Russian organism. When he describes the Russian fighting spirit the language is hardly generous, “Theirs is more a case of ‘dubious courage of suicide’ rather than the serene determination”. There is one prophetic line which might ring true for many contemporary International Relations : “Russia means whatever handful of men holds the reins and the knout at the same time be it the Emperor or a Commissar”. In his view from a diplomat’s perspective which I would hazard a guess reflects the then prevalent Western viewpoint that Russia really means nothing and can be understood. This is being written against the backdrop of Russian-Japanese power rivalry and it’s clearly manifest that Sands expresses sympathy with the Japanese side. Interestingly Sands expresses a sympathetic understanding for the Japanese hostility and suspicion where he writes: “One could understand what must be the Japanese state of mind confronted by it, without knowing exactly in what the menace might consist” referring to Russian antagonism at that time.

The Asian odyssey ends for Sands with a hurried voyage sailing back to Washington on a steam army transport ship Thomas amidst the Japanese gunfire attack on the Russian fleet at the Chemulpo Port with heavy columns of smoke rising. The Japanese sent across their Grand Fleet consisting of slender destroyers and formation cruisers to destroy the Russian ships in the harbour and this is the early onset of the Russian-Japanese war of the 1905 in which Japan secures a decisive victory against a Western power. This conflict as we know was perceived as the first victory of an Asian power over a Western one.

Apart from these broad trends of the geopolitical games and Court intrigues the book captures very vividly with a certain charm the routine life of an European with its joys and jubilations, trials and tribulations in a distant Eastern land of Korea. Sands elaborates with certain accurate and engaging detail the cuisine, the wine and the forms of entertainment engaged in by both the foreigner and local.

The book ends with a detached stoical philosophical note where Sands states he “rolled up the map of the Far East” as he headed towards a new assignment in Latin America. Finally, one was left wondering over these ‘undiplomatic memories’ of this young adventurous spirited US diplomat in the Far East.